Water quality issues in Germany and the UK – similarities and differences

by Siegfried Gendries with additional input by Cath Hassell

In the UK it is an offence to supply water unfit for human consumption under Section 70 of the Water Industry Act (1991) and similar legislation applies in Germany. Water supplied to buildings must be pure and suitable for drinking purposes without any health risks, containing neither pathogens nor other substances in health-damaging concentrations. To meet this legislation water suppliers deliver a constantly controlled drinking water supply, but their responsibility ends at the building boundary/water meter. Beyond this point the building owner or operator becomes responsible for the in-house drinking water supply system. While the water is transported by the utility company over many kilometres, usually with no deterioration in quality, sometimes only a few metres of pipework and associated fixtures and fittings within the building are enough to make the water no longer potable. Therefore, the last few metres are important to reduce risks but are not adequately covered by legislation.

While not all failures detected in tap samples are due to consumers’ plumbing, just over 24% of failures in England and Wales in 2016 were attributed to consumers’ domestic systems. This is either from poor plumbing practices, wrongly connected pipework, or sub-standard fixtures and fittings. The figure of 25% of water quality failures at customer’s taps as down to inadequate plumbing is likely to be similar in Germany and has led to some new thinking. Perhaps it is time we started thinking about drinking water as a food which is delivered into households on demand, and that more attention needs to be paid to the packaging. Because currently it seems very little thought is given to that aspect.

While German utilities are investing more than two billion euros annually in the public network and are regularly sampling the drinking water along the mains network, the house installations with their pipes and fittings have to meet certain standards when they are first installed, but after that, unlike cars with their annual MOT, are not subjected to any further testing. And, whilst building and plumbing regulations are updated fairly regularly (though in the UK the days of regulatory upgrades every ten years are now far away), regulatory changes usually apply to new buildings only with any retrospective requirements for domestic upgrades virtually non-existent. Thus the health risks from inadequate in-house installation in some older dwellings is unacceptably high, and there is little chance of them being inspected or upgraded.

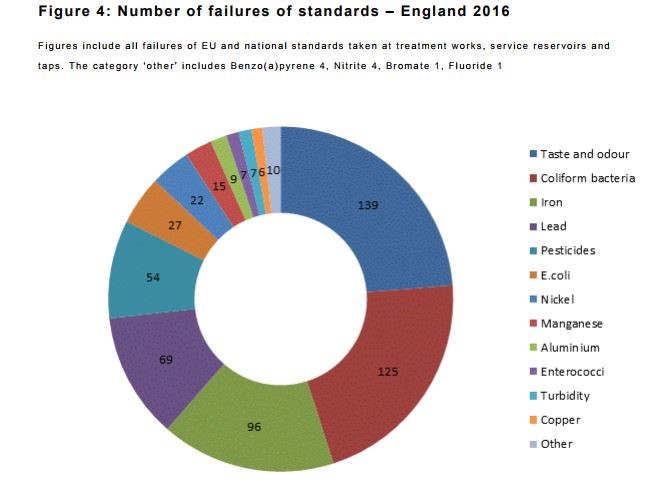

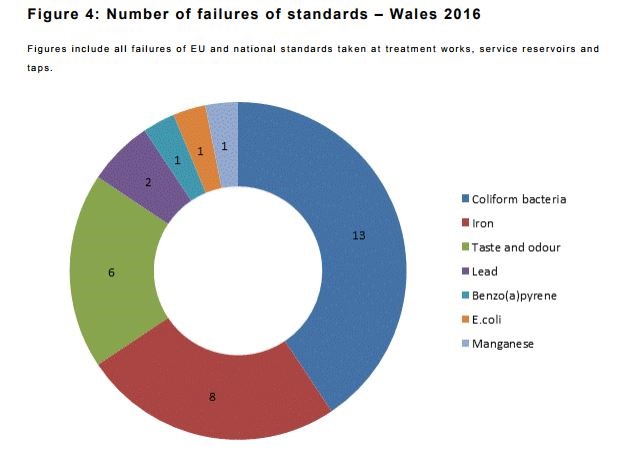

Failures of water quality in England and Wales in the mains network

The 2016 annual report of the Drinking Water Inspectorate (published in July 20171 ) confirmed that 99.96 per cent of the 3.9 million samples in England and 99.97 per cent of the 281,000 samples in Wales passed the required stringent water quality tests. Where failures do occur, 75% are due to breaches or other issues at either treatment works, service reservoirs or in the mains water network itself. Failures differ between the two countries. In England the most common failure is of taste and odour at 24%; in Wales it comes third (at 18% of failures) behind the presence of coliform bacteria and iron in the water. In Wales 41% of failures are from the presence of coliform bacteria compared to 21% in England. Contamination by iron is at 16% in England and 25% in Wales. Lead failures are at 12% in England and 6% in Wales while 9% of samples in England failed due to high level of pesticides compared to no failures at all in Wales.

There were eight serious event failures in 2016, all of which were in England. The most serious occurred in March 2016 when 3,700 properties supplied from the Castle Donington service reservoir, (Severn Trent Water) were instructed not to use their water due to a failure of the booster chlorination rig. A faulty valve allowed sodium hypochlorite (the disinfectant that produces chlorine) from the bulk tank to siphon into the service reservoir when an associated inlet main depressurised. Chlorine levels in the water supply rose as high as 8.8mg/l, compared to 0.5mg/l in normal operations.

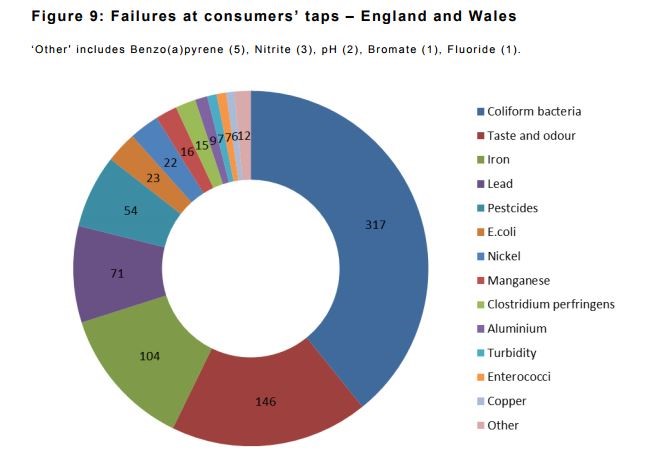

Failure of water quality England and Wales – at customer’s taps

Across England and Wales in 2016, the most prevalent detections at the consumers’ taps were for coliforms, taste and odour, iron and lead which accounted for 613 failures, a 68% increase between 2012 and 2016 of such events. Failures at taps from the presence of nickel (present in coatings on modern tap fittings which are widely available and approved) remain prominent with 22 failures in 2016.

Across England and Wales in 2016, the most prevalent detections at the consumers’ taps were for coliforms, taste and odour, iron and lead which accounted for 613 failures, a 68% increase between 2012 and 2016 of such events. Failures at taps from the presence of nickel (present in coatings on modern tap fittings which are widely available and approved) remain prominent with 22 failures in 2016.

An example of a failure within a building which then affected the wider network occurred in July 2016 when Yorkshire Water investigated reports of discolouration and an abnormal odour from a food manufacturer on an industrial estate in Thorne, near Doncaster. Samples taken identified bacteria of faecal origin and 3,648 properties were advised not to drink their tap water. The source was traced to a poultry processing factory on the same estate, with a recently installed mains-fed hot water system, which had been installed without notification (despite the requirement to be so under the Water Supply (Water Fittings) Regulations 1999. This hot water installation was a sealed system and the mains supply into the premises was not seen to be protected from backflow from the system by an appropriate air-gap or other backflow protection arrangement.

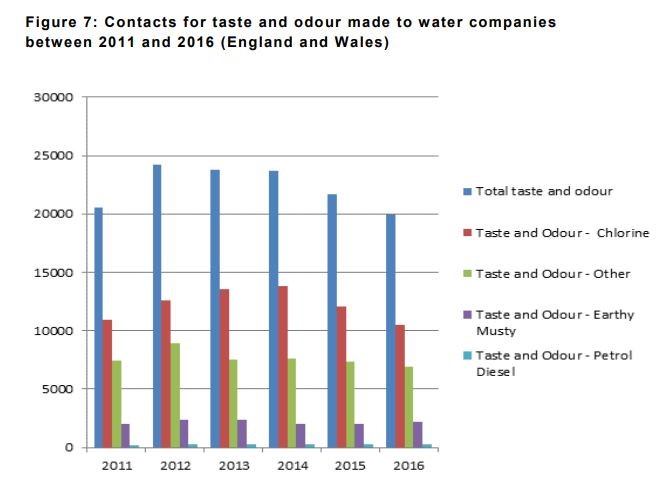

Failures of water quality in England and Wales for taste and odour

Taste and odour is the single most important means by which a consumer assesses the quality of food or drink and any failures under this parameter often have a significant impact on consumer confidence. The most common complaint is excess chlorine. Overall taste and odour complaints constituted 31% of compliance failures and 10% of events during 2016.

Taste and odour is the single most important means by which a consumer assesses the quality of food or drink and any failures under this parameter often have a significant impact on consumer confidence. The most common complaint is excess chlorine. Overall taste and odour complaints constituted 31% of compliance failures and 10% of events during 2016.

Water quality issues in Germany from stagnation

The stagnation of drinking water resulting from excessive water saving or empty flats is becoming a major issue in Germany, where water consumption has reached critically low levels in some regions especially in Eastern Germany. After reunification in the 1990’s water consumption rose rapidly to as high as 200 litres/person/day. This led to pressure on both the mains network and within blocks of flats themselves. So new blocks of flats were built with pipework sized for that level of flow rate, as were the supply lines laid to the blocks. Now, twenty years later, water consumption has fallen dramatically. On average German water consumption is 123 litres/person/day and in Saxony (former East Germany) it is as low as 83 litres/day. This means that pipes in large blocks of flats that were sized for a pcc of 200 litre are now oversized for the flow of water through them, resulting in drinking water stagnation with increasing risks of quality damages even in the summer period. In Germany, the landlord or operator of an in-house drinking water supply system must ensure by law that the quality of drinking water is not affected either by faulty behaviour or by other deficiencies. Many landlords are unaware of this requirement. Now, insurance companies are teaming up with water companies to generate awareness at the landlords or building operator’s level in order to prevent such occurrences happening and there is a concerted drive by water suppliers to encourage large landlords to implement on-going maintenance contracts using registered plumbers.

Kommentare